Every semester the community college Intro to Music course that I teach ends with a research assignment on American composers. Far and away the most common subject of these papers is Aaron Copland. When describing the quintessential American orchestral sound, that’s the name that many of us choose. So it’s mind blowing to consider that he was once brought to the United States Senate to testify about “un-American” activities.

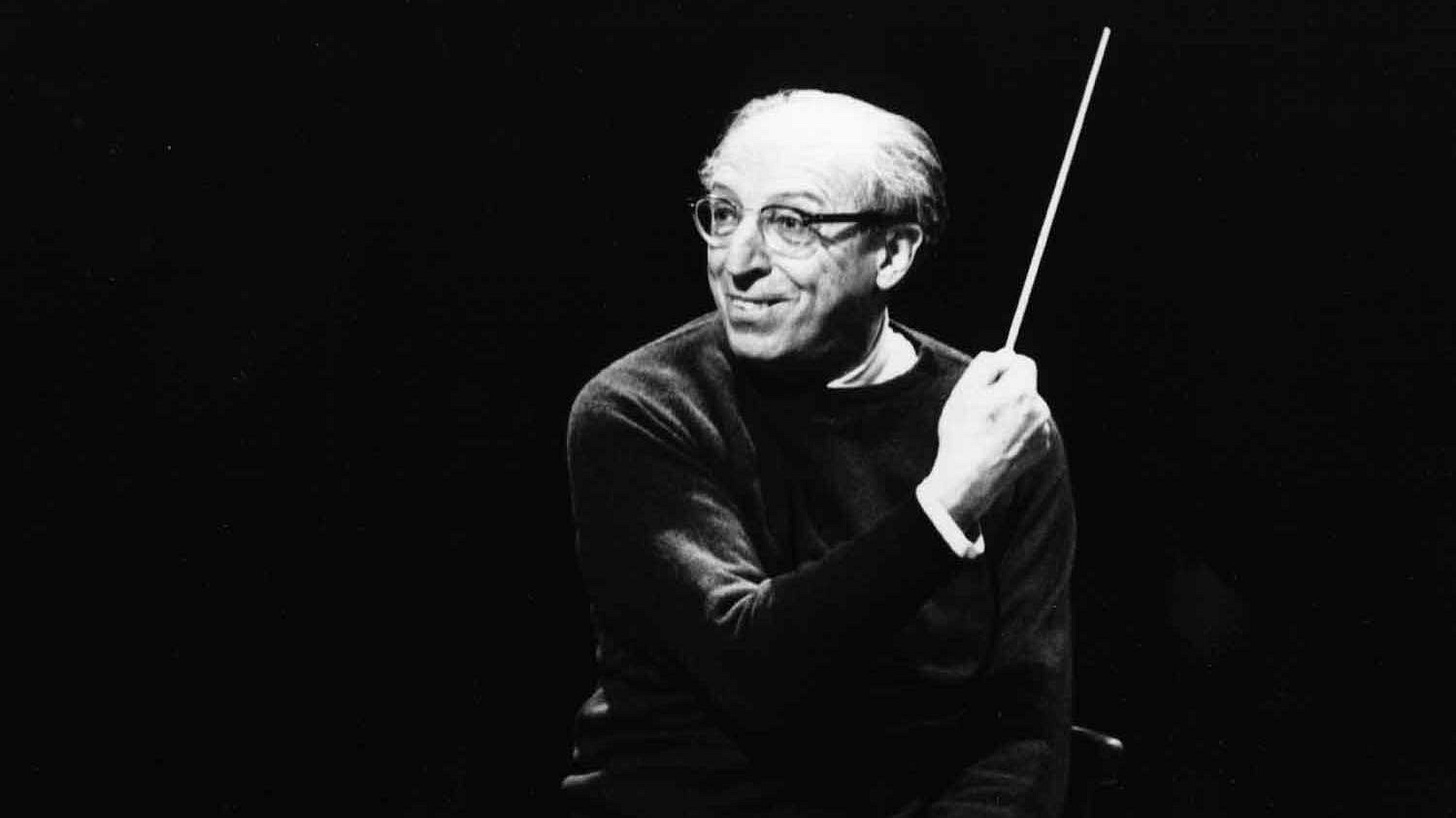

Yes, this Aaron Copland.

You’re doing a double take on the title of that fanfare, aren’t you?

While Copland lived until 1990, he’s best known for works he composed in the 1930s and 40s. In addition to the above Fanfare, that would be ballets like Rodeo:

And of course Appalachian Spring:

Born and raised in Brooklyn, and having studied composition in Paris, with visits to Mexico during the Great Depression, Copland was an unlikely choice to portray rural America in music, but he did so with lasting effect. And you might be thinking, “well sure, but it was easier for him! Times were different!” But you’d be missing a vital part of the story.

Aaron Copland’s status as Dean of American Composers became somewhat threatened in the mid 1950s, and it all started with a presidential inauguration.

The 1953 festivities to kick off Dwight Eisenhower’s first term included 65 musical units, 350 horses, 3 elephants, an Alaskan dog team, and the 280-millimeter atomic cannon. But one thing that was cut was this work:

Copland’s narrated orchestral piece Lincoln Portrait took its words from speeches and letters of Abraham Lincoln. It had premiered as the USA had entered WWII, and was programmed for a concert during the 1953 celebratory events, until a member of the inaugural committee asked, “wait a minute, isn’t that composer a communist?”

By May of that year Copland was compelled to head to Washington and testify in front of Joe McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigation.

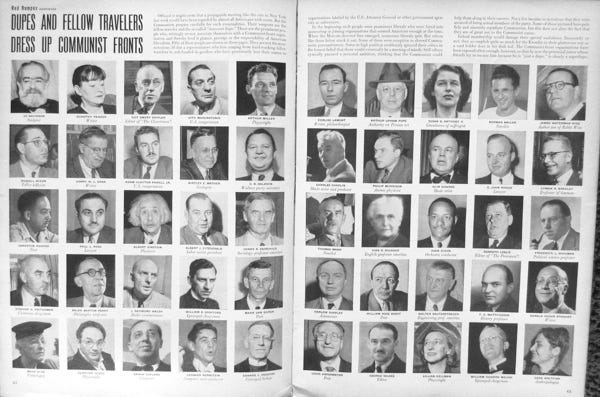

Copland never actually joined any political party at all, though his progressive beliefs were no secret, and he did at one time vocally support more than one political candidate who was an affiliated communist. And he had participated as a speaker at an international gathering in 1949 called the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace. Life magazine described the event’s host, the National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions, as “dominated by intellectuals who fellow-travel the Communist line.”

That’s an attendees list that also included Langston Hughes, Arthur Miller, Charlie Chaplain, Dorothy Parker, Leonard Bernstein, and Albert Einstein (as well as a Russian delegation of 7, which included composer Dmitri Shostakovich). I know this because Life listed these attendees under the headline “Dupes and Fellow Travelers Dress Up Communist Fronts.” The article sent shockwaves through the intellectual world - one professor committed suicide after he was named as a participant.

In the May 1953 senate hearing Copland was actually questioned by Donald Trump’s mentor Roy Cohn. After learning that the committee was exploring his association with 27 total organizations, Copland expressed that he was astounded at the number. Cohn answered, “so were we.” Ominous, but also somewhat evident that the committee really didn’t know what to make of the composer.

Copland also retained his dignity. He was never hostile in his testimony, but he was certainly never cooperative, and he gave zero names. Essentially, he described his interests as simply musical rather than political.

By this point Copland had already started distancing himself from political organizations, and was especially wary of communism after the Soviet government’s poor treatment of Dmitri Shostakovich.

The investigation of Aaron Copland didn’t stop for two years, and his case only technically closed in 1975. During that time he had trouble getting a passport, which he needed for trips like in 1960 when the US State Department entrusted him (still under investigation) with a diplomatic tour of the USSR.

This story could easily have happened today: controversy at an inauguration, a political witch hunt (with the influence Roy Cohn), plus a tense relationship with Russia. It’s also a story that feels appropriate for a time when many of us are asking ourselves what it means to be an American, never mind an American musician.

In the mind of many in the general public, being an American composer means being Aaron Copland. But what is “being Aaron Copland” like in practice? He was consistently politically engaged. He loved other men openly, and thus he was subjected to not only the red scare, but also the lavender scare. He was called to the US Senate to answer question after question about his loyalty, seemingly because he worked as a teacher, and composed an ode to democracy.

Throughout his career Copland remained a steadfast advocate for his fellow composers, at home and abroad. He adapted to the Great Depression, and the newly popular media of radio and film. He looked Joe McCarthy in the face, and calmly told him it was his right to stand firm in his beliefs. This is not someone who wrote a few hits and then got to coast off of the residual glory. Aaron Copland was a survivor who remained true to himself. Fanfare for the Common Man is the perfect example.

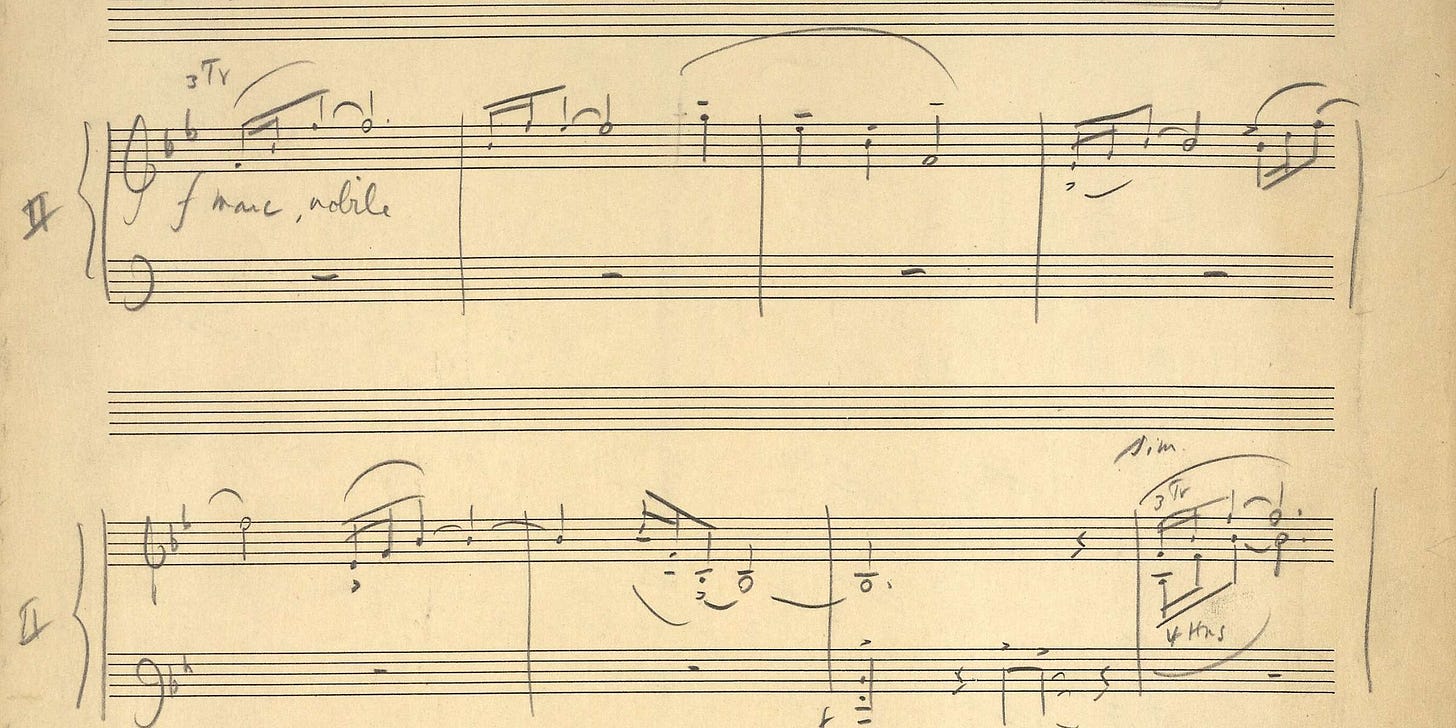

In 1942 the Cincinnati Symphony had commissioned a series of concert openers, including one from Copland to support the US entry into World War II. Other entries had militaristic titles: Fanfare for the American Soldier and A Fanfare for the Fighting French for example. But Copland didn’t deliver his until a bit later in the orchestral season. And when he did, he chose a title inspired by a speech from Henry Wallace, stating that the post-war century should be the “century of the common man.”

It was conductor Eugene Goosens’ idea to premiere the work near the filing deadline for income tax - a great way to make the most of the title. Of the ten fanfares that the CSO premiered that year, it’s the only one that has remained in the repertoire. Unlike Lincoln Portrait, it has since been performed at multiple presidential inaugurations.

It’s not a flourished fanfare. It’s simple, slow, noble, powerful. In Copland’s words, it “honors the man who did no deeds of heroism on the battlefield, but shared the labors, sorrows and hopes of those who strove for victory.” In fact, its simplicity forces the players to work together, since it gives them nowhere to hide. They have to move as one, locked in and quite literally breathing together.

Four years later in 1946, Aaron Copland saw the Boston Symphony premiere his third symphony. He offered no program notes, suggesting that the music “speak for itself.” The fourth movement certainly made a statement, opening with a direct and extended quotation of Fanfare for the Common Man.

Boston critics didn’t know what to say about the work. Some referred to it as “Copland-esque” (duh). But a couple of others, 7 years ahead of Joe McCarthy, compared him to a Soviet Russian composer - Shostakovich. Yet another even mentioned Richard Strauss, whose name was still tied up in his connections to the Third Reich at the time. It was fellow composer Virgil Thompson whose review was later reprinted in Boston Symphony program books. Despite his analysis not being entirely positive, he does describe what “Copland-esque” might mean.

“Copland aspires, I assure you, to no Jove-like pronouncements. Nor is he any double-tongued oracle. He is much more, for all his skill and personal enlightenment, Henry Wallace's ‘Common Man.’”

He said the thing!

There’s a reason Copland’s music is iconic for Americans. It’s not just the melody, it’s the sentiment behind it. The belief in the “common man.”

There is a lot to challenge us in the USA right now. When a symbol of hate is downplayed as a joke. When natural disasters seem to follow one after another. When yet another school shooting hits incredibly close to home. When a member of congress called for the deportation of a US citizen just because she, a bishop, dared to preach mercy. The news cycle will make your head spin.

As American musicians it’s important to ask ourselves what our role is in such a tempestuous time. I think Copland gives a decent model for one way forward. His catalog is a reminder that music making has a purpose - to remind us of our humanity. And it gives us an outlet to share our hopes for the world. As World War II began and Copland’s Lincoln Portrait premiered, the composer knew the importance of his task.

“Music no less than machine guns has a part to play, and can be a weapon in the battle for a free world.” - Aaron Copland

With our music we can challenge each other, and uplift each other. We can tell important stories, and shine a light in the darkness. Because there are a lot of us, this so-called “common man.” And it’s our place to take care of each other.

-Colleen

P.S. - There’s more to the story of musicians and McCarthyism. Singer Paul Robeson’s passport was illegally confiscated before he appeared in the House of Representatives. Composer Marc Blitzstein was called to the House for questioning. Leonard Bernstein had a rather full FBI file.

Anyone who reaches for classical music to avoid politics is missing out on a great deal of history.

“‘Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history’

That is what he said,

That is what Abraham Lincoln said…” - Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait