The "Four"boding

Brahms, his fourth symphony, and the little voice in the back of your mind

“Now you will hear a real piece!” - Johannes Brahms, to a friend before his last concert

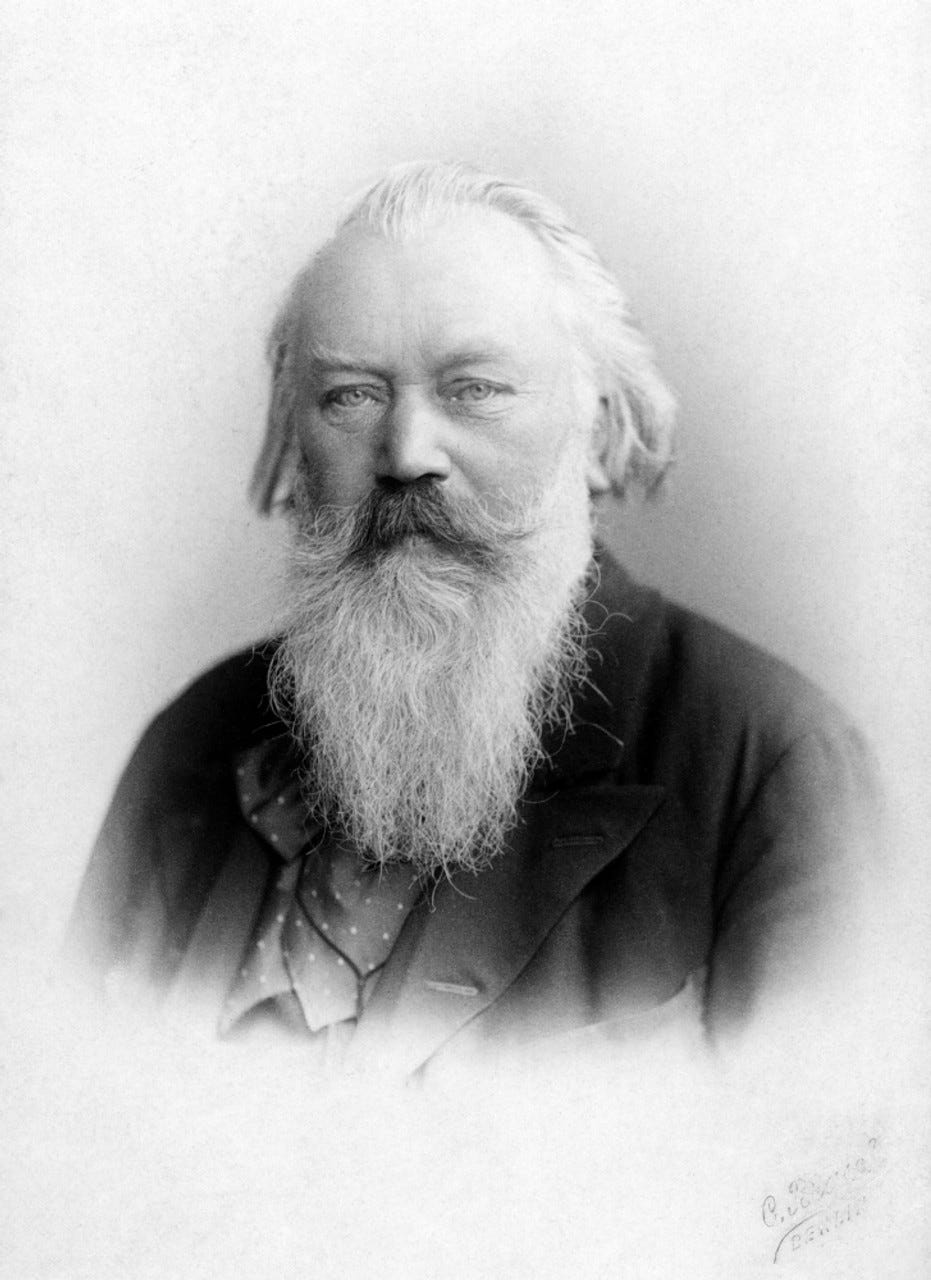

On March 7, 1897, Johannes Brahms attended a concert featuring his own music for the last time. The composer was suffering from cancer, and it was not secret that he was ill. The quote above does not refer to his piece - it’s about Antonin Dvorak’s cello concerto, which was also on the program.

Nobody did self-deprecation like Brahms.

At the end of the evening Brahms took a long bow before the crowd, whose warmth seemed to indicate that they knew this was their farewell. The piece? His fourth symphony. A work that, when placed into its historic context, is one that merits a closer look today.

Brahms was working on his fourth symphony 12 years before that final concert, at a time when politics in Vienna were taking a sharply dark turn. Georg Schönerer was already calling for the Anschluss, and being addressed by the title Führer. Karl Leuger, who was also quick to exploit antisemitism, had just been elected to parliament. This was decades after Richard Wagner’s essay Jewishness in Music had been published, criticizing composer like Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer as not being able to produce “true German” art.

Wagner is important in this discussion because his followers had established a binary: Wagner as the future of German music, and Brahms as the past. The perceived insulting nickname they hurled at Brahms was “der Jude.” If anything, Brahms was Lutheran (albeit unorthodox), so this might not make sense to our modern context. But at the time, from that crowd, it was a slur indicating someone was cosmopolitan, decadent, or simply “other.” It was a way to say they weren’t authentically German. Brahms took offense at the inaccuracy, but not the name itself, at one point saying he would just simply “get circumcized tomorrow.”

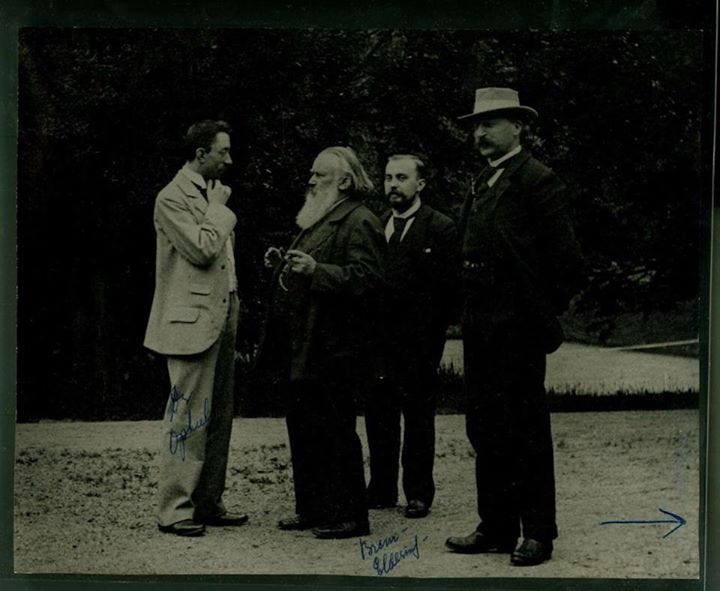

The circle of friends that Johannes Brahms held dear would also indicate that he was not going to fall for antisemitic rhetoric. He remained close with Joseph Joachim, Karl Goldmark, Ignaz Brüll, and Eusebius Mandyczewski.

“Wahnsinn.” [“madness”] - Johannes Brahms on antisemitism

Unlike Wagner, Brahms wasn’t one for a manifesto or a public debate. But that doesn’t mean he just went with the flow or didn’t care about the state of the world. His values skewed humanist. He was skeptical to dogma, and compassionate to individuals. The same guy who composed the Triumphed to celebrate victory after the Franco-Prussian War began spending summers in Switzerland because he was angry over the conservative coalition (the quasi-clerical, so-called “Iron Ring”) in the Austrian parliament.

Johannes Brahms felt alienated. He was watching a political faction use religion and nationalism in order to be less tolerant. His friends were under constant attack. I doubt he knew where it would lead within 50 years. Who could possibly have known? But he certainly expressed his unease, both in words and music.

And that’s where his fourth symphony comes in.

As does the composer’s tendency to minimize his own efforts.

“Once again I’ve just thrown together a bunch of polkas and waltzes.” - Brahms on his fourth symphony

Around that time Brahms had written to his publisher, saying that everything in Austria was tumbling downhill, and music right along with it. For “the whole beautiful land and the beautiful marvelous people” he presaged, “I still think catastrophe is coming.”

This wasn’t precisely an unusual sentiment for Brahms, who was in many ways the consummate mourner in music. His German Requiem walks gently through the sadness, consolation, and hope. Beginning with a benediction, and bringing the sentiment to earth in the middle, offering “How lovely are thy dwellings?”

And his Song of Fate, which asks “who can heal our pain?”

But there’s no way that in his letter to his publisher Brahms was only referring to his own crisis. When Karl Leuger was later elected Mayor of Vienna in 1895 Brahms shouted to his friends that he told them it would happen. They had laughed at the very idea of Leuger being elected, and it still happened.

Antisemitism in Vienna was crushing the middle class, of which Brahms was a member. He feared that both his friends and his music would be destroyed along with it. This distinct unease permeates the symphony. The second movement, which borders on being a funeral march, slowly ratchets up tension that never seems to go anywhere.

And the third movement feels like it’s going to head somewhere good, but the momentum keeps getting cut short. It’s a level of playing sarcastically with the audience that to my mind presages Shostakovich.

The fourth movement is an exercise in inevitability. The repetition of a passacaglia that isn’t reassuring - it’s inescapable. A struggle with tension that doesn’t actually resolve with any kind of triumph.

Johannes Brahms was just 63 when he heard the work played for the last time, in that 1897 concert of the Vienna Philharmonic, where nobody could possibly have known what was to come for Europe in the next few decades. …Or could they?

But more importantly, when you’re worried about the end of the world, why bother to put it in music?

If Brahms had only written a manifesto saying “I think we shouldn’t discriminate against a whole religion,” would anyone pay attention today? If Shostakovich had merely composed a magazine article that said, “authoritarians are bad,” would we know his name? If Beethoven had burned his third symphony in the fireplace rather than changing the title, would we care how he felt about Napoleon?

We know and care because we have the music, not the other way around. We listen first, then we understand. We hear the triumph in Beethoven’s third and think “Who is that about?” We are shocked by the intensity of Shostakovich’s fifth and wonder who was after him?

“That guy was going through some stuff, right?” - my son, hearing Shostakovich 5 for the first time

What’s amazing about Brahms’s fourth is that he’s not quite there in the thick of it yet. Somewhat - things are happening, but we’re not sure how bad they might get. It’s only the first act. That unease is not familiar to us in a symphony. And rather than the defiance or wistfulness that were usually able to identify, the lack of surety is in itself a shock.

Three weeks ago in 2025 it felt like political rhetoric couldn’t get any more divided, and then it did. Vienna probably felt that way in 1885. Casting each other as enemies rather than individuals is not anything new in the course of history, and it’s so often the place where we wish we could go back in time and say “calm down!” I would love to plant a flag on Brahms 4 and say “you are here” but I’m honestly not sure if we’re past it. That can only be analyzed with hindsight.

A symphony is a snapshot of a place and time. One that can speak to us in a way that words even cannot.

The question to ask ourselves as we listen to a work like Brahms’s fourth is an important one: Does it feel familiar? And if so, what do we wish would have happened in that history, after that snapshot? The thing about a warning is that it actually gives us a choice. In this case, to take good look at the words we use for each other, the way we point fingers, and the blame we assign. A look at the damage we can do when we forget each others’ humanity

Listen to the music. Say, hypothetically, “you are here.” What now?

-Colleen

PS: I feel compelled to add some good news to this newsletter today. So enjoy my friend Laura Atkinson’s coverage of the update of The Sacred Harp. Read it via NPR.

Colleen,

I love this line: "A symphony is a snapshot of a place and time. One that can speak to us in a way that words even cannot."

Thank you for continuing to educate and inspire us. By the way, the piece you played earlier this morning from the movie, "The Hours" was absolutely exquisite!

The parallels with today are indeed frightening. I hadn’t been aware of Georg Schönerer; your reference led me to look him up. Thank you for this history and context behind Brahms’ Fourth!